Fairfield Porter Painting of Seated Woman in White Dress

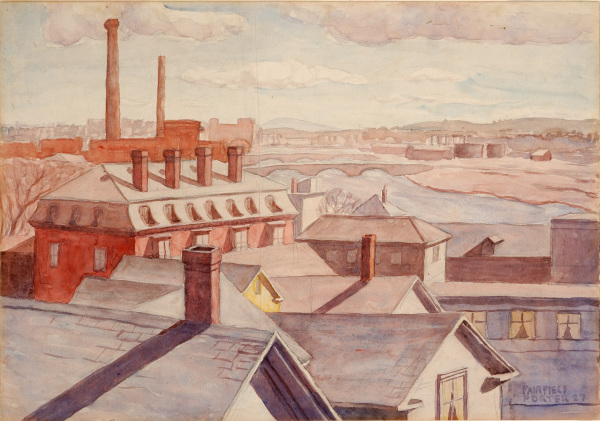

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), Roofs of Cambridge, 1927. Watercolor on cardboard, 13 7/8 x 20 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift of the Estate of Fairfield Porter, 1980.10.120

Fairfield Porter studied at Harvard College, graduating in 1928; some 20 years later, Cambridge was also the meeting place for Kenneth Koch, John Ashbery, and Frank O'Hara, three young poets whose work would come to be known as the New York School. Both Porter and O'Hara find ample artistic inspiration in the chill of a New England morning.

CAMBRIDGE, 1957

Frank O'Hara (American, 1926–1966)

Read by Max Blagg

It is still raining and the yellow-green cotton fruit

looks silly round a window giving out on winter trees

with only three drab leaves left. The hot plate works,

it is the sole heat on earth, and instant coffee. I

put on my warm corduroy pants, a heavy maroon sweater,

and wrap myself in my old maroon bathrobe. Just like Pasternak

in Marburg (they say Italy and France are colder,

but I'm sure that Germany's at least as cold as this) and,

lacking the Master's inspiration, I may freeze to death

before I can get out into the white rain. I could have left

the window closed last night? But that's where health

comes from! His breath from the Urals, drawing me into flame

like a forgotten cigarette. Burn! this is not negligible,

being poetic, and not feeble, since it's sponsored by

the greatest living Russian poet at incalculable cost.

Across the street there is a house under construction,

abandoned to the rain. Secretly, I shall go work on it.

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), John, Richard, and Laurence, ca. 1950. Oil on canvas, 45 3/4 x 45 1/2 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift of the Estate of Fairfield Porter 1982.9.7

The painting of Porter's three sons, seated at the dining room table at 49 South Main Street, is a complex portrait of his relationship with each; the artist's poem is a further probing of these feelings.

The Loved Son, n.d.

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975)

Read by Alicia Longwell

When a loved son turns his back and goes

Down the street on a bicycle become too small

His overcoat flapping absurdly behind him

Maybe only as far as the beach

My heart is suddenly wrenched out of me

And I might as well let go and be done with it

And stay heartless, for what use could regret be

If my heart must no longer follow him?

When the grown boy turns his back and leaves

Looking forward to college or even the army

Glad to be grown up happy to be gone

Counting his new dependence as independence

I think how carelessly I have regarded him

With what little penetration I have known him

And have not listened to the pleasant wit

That marks the shrewdness of his watching mind.

In whatever new place for a short time his home

Surrounded by companions of his own age

Carrying with him no baggage of infancy

But the disappearing scars of his childish wounds

His new friends now, freshly for the first time

With contemporary easy intimacy

In a flash of insight looking in his eyes

Know the depths of his being and love him instantly.

Robert Dash (American, 1931–2013), Afternoon #2, 1965. Oil on canvas, 60 x 60 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y. Gift of the Madoo Conservancy, 2014.25.1

In the summer of 1955, poet Barbara Guest rented the Porter's Southampton house for $500 when the Porter family departed for Maine. Her poem evokes the mystery and ambiguity of an old house, also suggested by Robert Dash's lyrical painting of the view from the Porter's front hall into the living room.

Escape, ca. 1945

Barbara Guest (American, 1920–2006)

Read by Patricia Maurides

After so many hours spent in the room,

One wonders what the room will do.

Whether speech or action will be first,

And whether the weather will be first

To begin.

Such long inaction is unnatural.

But why should it happen to you, when

Outside, the street has silver cars,

All unoccupied, equipped and ready

For departure? Even the kitchens

Are ready with pans, and the dishes for something

Heretofore unplanned. The people who pass

Whisper and stare, then say, "house."

Why not accept the waiting and forego

The known? After all,

Occupancy is only a matter of making up

One's mind. The silver cars are square

And the room is long.

Interruption would be different in a car.

It would come on the road, like trees and fern.

Like the flowers whose names have been learned.

Or sandwiches made in layers; the friction

Would be brief and quickly swallowed.

Not people. Not the stranger with the listening

Heart, or the girl without a mind. Not

Person. The encroachment would be barely

Visible. It would happen on a side road,

A detour, or a highway cut by mistake.

You would wipe it off like the windshield

And be ready for the next advance.

After all, this house is old.

How many people come creeping,

After the spider, upstairs. Some with bags

And some with baskets, and all going nowhere. They

Only want to settle under the roof like pigeons;

Quarter their young and prepare for the future.

But you are different. You have watched

The vanishing of the separate ghosts. You have seen,

Over the bannister, the disappearance

Even of those who tried to remain.

You should not wait for the walls

To speak. Go into the bathroom,

Turn on the faucet, and swim into the street.

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), Lunch under the Elm Tree, 1954. Oil on canvas, 78 x 59 7/8 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift of the Estate of Fairfield Porter, 1980.10.65

Porter shared with his poet friends an endless fascination with the ordinary moments of life. On an extended trip abroad, Koch takes a moment to celebrate one particular seaside lunch in France with detail and humor that elevates the midday meal, when it finally arrives, to an epiphany. Porter's towering elm tree dominates a scene in the backyard of 49 South Main, dwarfing the lunch party seated beneath.

Lunch, 1962 (Excerpt)

Kenneth Koch (American, 1925–2002)

Read by Alicia Longwell

Oh I sat over a glass of red wine

And you came out dressed in a paper cup.

An ant-fly was eating hay-mire in the chair-rafters

And large white birds flew in and dropped edible animals to the ground.

If they had been gulls it would have been garbage

Or fish. We have to be fair to the animal kingdom,

But if I do not wish to be fair, if I wish to eat lunch

Undisturbed –? The light of day shines down. The world continues.

We stood in the little hutment in Biarritz

Waiting for lunch, and your hand clasped mine

And I felt it was sweaty;

And then lunch was served,

Like the bouquet of an enchantress.

Oh the green whites and red yellows

And purple whites of lunch!

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), Katie at the Table, ca. 1953. Oil on canvas, 32 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y. Gift of the Estate of Fairfield Porter 1980.10.53

On his many visits with the Porter family, in Southampton and on Great Spruce Head, O'Hara and the Porters' oldest daughter Katherine developed a special bond through their love of writing. O'Hara later published this poem as a collaboration between himself and six-year-old Katie.

KATY, 1953

Frank O'Hara (American, 1926–1966)

Read by Patricia Maurides

They say I mope too much

but really I'm loudly dancing.

I eat paper. It's good for my bones.

I play the piano pedal. I dance,

I am never quiet, I mean silent.

Some day I'll love Frank O'Hara.

I think I'll be alone for a little while.

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), Sketch for Portrait of Jimmy Schuyler, ca. 1962. Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 x 30 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift of the Estate of Fairfield Porter, 1982.9.12

In the introduction to a collection of Fairfield Porter's poetry (published posthumously in 1985), his friend John Ashbery recalls that Porter's poetry "mattered a lot to him. . . and he indeed wondered what various friends thought of his verses, but doesn't seem too worried about it." In this musing, Porter seems to delight in describing the quirks and traits of his circle of friends.

I wonder what they think of my verses, n.d.

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975)

Read by Alicia Longwell

If Jimmy likes them, I believe him

Because Jimmy is kind

And he does not pretend

If Larry dislikes them, I do not believe him

Because his ambition distracts him

If John dislikes them, I believe him

Because he is lazy and quick

If Franks likes them or dislikes them, I do not believe him

Because Frank is considerate

And he is led by his imagination

Far beyond the ability to forgive

If Jane likes them, I believe her

Because her feelings guide her

And if Anne is critical I believe her

Because she desired my credit

If Rudy is impressed

It is because he did not know I had it in me

If Walter dislikes them

He does so to prove his affection

If Edwin understands them

It is to reciprocate my trust

And Kenneth is pedantic

And filial and fatherly

But Jerry is contemptuous and sarcastic

Because he wants me to love him

And Laurence admires them

Because he wants to admire his father

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), Penobscot Bay with Yellow Field, 1968. Oil on canvas, 38 1/4 x 55 1/4 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift of the Estate of Fairfield Porter, 1980.10.148

The sestina is surely one of the most complex ways of composing a poem but Porter and the New York School poets took delight in the intricate challenge of the form. Here Ashbery investigates the making of a work of art.

The Painter, 1956

John Ashbery (American, 1927–2017)

Read by Patricia Maurides

Sitting between the sea and the buildings

He enjoyed painting the sea's portrait.

But just as children imagine a prayer

Is merely silence, he expected his subject

To rush up the sand, and, seizing a brush,

Plaster its own portrait on the canvas.

So there was never any paint on his canvas

Until the people who lived in the buildings

Put him to work: "Try using the brush

As a means to an end. Select, for a portrait,

Something less angry and large, and more subject

To a painter's moods, or, perhaps, to a prayer."

How could he explain to them his prayer

That nature, not art, might usurp the canvas?

He chose his wife for a new subject,

Making her vast, like ruined buildings,

As if, forgetting itself, the portrait

Had expressed itself without a brush.

Slightly encouraged, he dipped his brush

In the sea, murmuring a heartfelt prayer:

"My soul, when I paint this next portrait

Let it be you who wrecks the canvas."

The news spread like wildfire through the buildings:

He had gone back to the sea for his subject.

Imagine a painter crucified by his subject!

Too exhausted even to lift his brush,

He provoked some artists leaning from the buildings

To malicious mirth: "We haven't a prayer

Now, of putting ourselves on canvas,

Or getting the sea to sit for a portrait!"

Others declared it a self-portrait.

Finally all indications of a subject

Began to fade, leaving the canvas

Perfectly white. He put down the brush.

At once a howl, that was also a prayer,

Arose from the overcrowded buildings.

They tossed him, the portrait, from the tallest of the buildings;

And the sea devoured the canvas and the brush

As though his subject had decided to remain a prayer.

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), Jane and Elizabeth, 1967. Oil on canvas, 55 1/8 x 48 1/8 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift of Jane Freilicher, 1979.13.2

When James, most often called Jimmy, Schuyler first became friendly with fellow poets Ashbery, Koch, and O'Hara in the early 1950s, Koch later recalled that Schuyler "passed one test for being a poet of the New York School by almost instantly going crazy for Jane Freilicher and all her work." In this poem to Freilicher, Schuyler closely identifies the artist with the cycles of nature.

Looking Forward to See Jane Real Soon, n.d.

James Schuyler (1923–1991)

Read by Max Blagg

May drew in its breath and smelled June's roses

when Jane put roses on the sill. The sky,

in blue for elms, planted its lightest kiss,

the kind called a butterfly, on bricks fresh

from their kiln as the roses from their bush.

Summer went by in green, then two new leaves

stood on the avocado stem. The sky

darkened the color of Jane's eyes and snow

wrote her name in white. Such wet snow, that stuck

to the underside of curled iron and stone.

Jane, among fresh lilacs in her room, watched

December, in brown with furs, turn on lights

until the city trembled like a tree

in which wind moves. And it was all for her.

Fairfield Porter (American, 1907–1975), Anne, 1965. Oil on canvas, 47 x 38 inches. Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, N.Y., Gift of the Estate of Fairfield Porter, 1980.10.186

Porter painted his wife countless times during their forty year marriage—here on the porch of the house in Great Spruce Head where her figure almost merges with the weathered gray clapboard exterior. Anne Porter's poem recounts a trip that she and Fairfield made shortly before their marriage and her understanding, from that moment on, of the unassailable bond between them.

Lovers

Anne Channing Porter (1911–2011)

Read by Alicia Longwell

I can still see

The new weather

Diamond-clear

That flowed down from Canada

That day

When the rain was over

I can still see

The main street two blocks long

The weedy edges of the wilderness

Around that sawmill town

And the towering shadows

Of a virgin forest

Along the log-filled river

We walked around

In a small travelling carnival

I can still hear

Its tinny music

And smell its dusty elephants

I can still feel your hand

Holding my hand

That day

When human, quarrelsome

But stronger

Than death or anger

A love began.

Source: https://parrishart.org/poems/

0 Response to "Fairfield Porter Painting of Seated Woman in White Dress"

Post a Comment